The year is 12011. Two hikers cut through a stretch of cactus-filled desert outside what was once the small town of Van Horn, near the Mexican border, in West Texas. After walking for the better part of a day under a relentless sun, they struggle up a craggy limestone ridge. Finally they come to an opening in the rock, the mouth of what appears to be a long, deep tunnel.Via: IEEE Spectrum

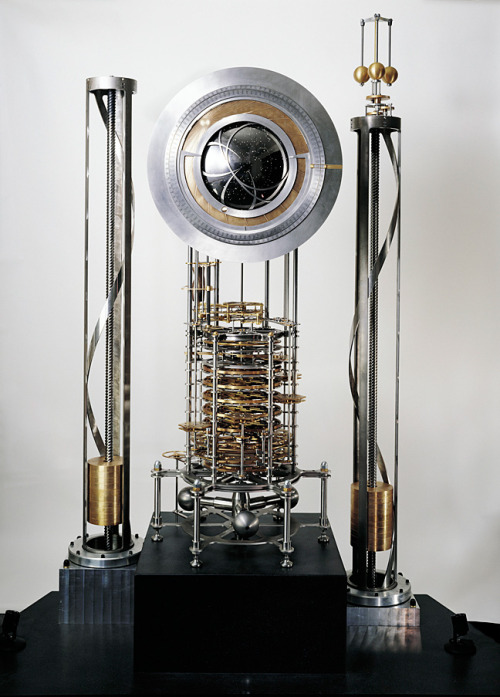

As they head into the shadows, not quite knowing where the tunnel will lead, the sudden darkness and the drop in temperature startle their senses. After a few minutes the hikers reach a cool chamber dimly lit from above. A tall column of strange shiny metal gears and rods rises hundreds of meters above them. Steps cut into the walls spiral upward, and the hikers ascend until they reach a platform. A black globe suspended above depicts the night sky, encircled by metal disks that indicate the year and the century.

A giant metal wheel sits in the middle of the platform, and the visitors each grasp a handle that juts out from its smooth edges. For the next several hours, they push and walk and push and walk in a circle, methodically, silently, until the wheel will turn no further. Exhausted, they rest on the platform and drift off to sleep. At noon the next day, they’re suddenly awakened by the ethereal tones of chiming bells.

It sounds like science fiction, but this is the real vision for the 10 000-Year Clock, a monument-size mechanical clock designed to measure time for 10 millennia. Danny Hillis, an electrical engineer with three degrees from MIT who pioneered parallel supercomputers at Thinking Machines Corp., worked for Walt Disney Imagineering, and then cofounded the consultancy Applied Minds, dreamed up the project in 1995 to get people thinking more about the distant future. But the clock is no longer just a thought experiment. In a cluttered machine shop near a Starbucks in San Rafael, Calif., it’s finally ticking to life.

Art Resources

▼

No comments:

Post a Comment